All scripture is God-breathed and is useful for teaching, rebuking, correcting, and training in righteousness, so that the man of God may be thoroughly equipped for every good work.”

- 2 Timothy 3:16

“Above all, you must understand that no prophecy of Scripture came about by the prophet’s own interpretation. For prophecy never had its origin in the will of man, but men spoke from God as they were carried along by the Holy Spirit.”

- 2 Peter 1:21-22

“Teacher, what is the greatest commandment in the Law?” Jesus replied: “Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind. This is the first and greatest commandment. And the second is like it: Love your neighbor as yourself. All the Law and the Prophets hang on these two commandments.”

- Matthew 22:36-40

"I am the Lord your God, who brought you out of Egypt, out of the land of slavery.

- You shall have no other gods before me.

- You shall not make for yourself an idol in the form of anything in heaven above or on the earth beneath or in the waters below…

- You shall not misuse the name of the Lord your God, for the Lord will not hold anyone guiltless who misuses his name.

- Remember the Sabbath day by keeping it holy. Six days you shall labor and do all your work, but the seventh day is a Sabbath to the Lord your God. On it you shall not do any work…

- Honor your father and your mother, so that you may live long in the land the Lord your God is giving you.

- You shall not murder.

- You shall not commit adultery.

- You shall not steal.

- You shall not give false testimony against your neighbor.

- You shall not covet…anything that belongs to your neighbor.”

- Exodus 20:2-17 (numbering added; see also the similar passage in Deuteronomy 5:6-21)

As will be discussed in more detail in the final section of this site on Evidence for the Authority of the Bible, the Bible claims to be the divinely inspired Word of God, and as such, to be an authoritative guide to both moral and spiritual life. However, this site will focus primarily on the moral principles taught in the Bible (i.e., the principles governing our relationships with one another),[1] and will leave detailed discussion of our spiritual or religious duties to God to the church (or synagogue or mosque) and/or to each individual’s conscience.

Furthermore, I wish to make it clear from the outset that I am not advocating a theocratic state, in which the laws of the state are synonymous with the laws of one particular religion. I recognize that such a state would violate the guarantee of religious freedom that America’s founding fathers intended us to have. Instead, I am advocating a truly free “marketplace of ideas” in which Americans of all religions (or no religion) are equally free to express their religious convictions (or lack thereof) in the public square. For purposes of this site, I will be discussing the Bible only as a clear guide (and as the guide with which Americans are most familiar), to what America’s founding fathers referred to as the “Laws of Nature,” the “natural law,” or the “moral law,” which is in fact our common morality, that we all know in our hearts is right.

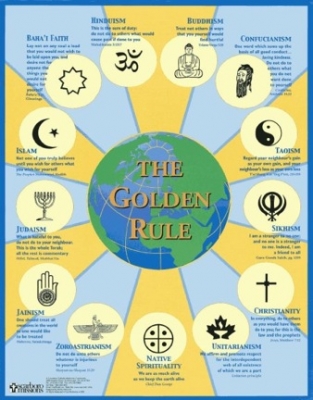

As an example of how universal our common morality really is, consider the principle of “do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” This is a restatement of one of the two greatest commands of Christianity and Judaism (“love your neighbor as you love yourself,”) but it also appears in the teachings of many other major religions of the world, including secular humanism.[2]

The chart below (from Scarboro Missions in Canada) shows how the principle of “do unto others as you would have them do unto you” is common to many of the world’s religions:

The same rule is also found (though it may not be regarded as supreme) in both ancient and modern systems of secular thought:

- Ancient Roman: “The law imprinted on the hearts of all men is to love the members of society as themselves.”

- British Humanist Association: “Treat other people as you'd want to be treated in their situation; don‘t do things you wouldn't want to have done to you.”

Furthermore, since “do unto others as you would have them do unto you” is in fact a summary of the natural law, there is also much common ground in the other teachings of various world religions about how we should relate to one another (i.e., do not murder, do not commit adultery, do not lie, cheat, or steal.)

This similarity in moral codes among different religions is the basis for the often-heard (although somewhat inaccurate) claim that “all religions are the same” that has become popular in some parts of American society. In fact, although different religions often have very different theology (different beliefs about God – for example, Christianity, Judaism, and Islam have very different beliefs about Jesus, and his divinity or lack thereof), different religions do generally have similar codes of morality (or similar beliefs about how we should relate to one another.) For example, although different religions (or different systems of secular thought) may have somewhat different ideas about what the correct definition of stealing is, or what is the appropriate punishment for it, no one seriously attempts to argue that stealing is good. The same can be said for many other vices such as lying, envy (or greed or covetousness), and adultery.

Another way to see how universal our common morality really is is to remember how you felt the last time someone lied to you, cheated you, or stole from you. We all have an innate sense of moral outrage or moral violation in such situations, and often this sense of moral violation hurts as much as or more than the material loss caused by the deception or theft.

Arguing also requires at least an implicit reference to some universal moral standard. The whole idea of trying to show that we are “right” and another person is “wrong” would be meaningless unless there is in fact some universal moral standard to which we can all appeal, and which we are all capable of understanding.

The value of keeping the natural law (or the cost of breaking it) can often also be supported by objective data from the physical and social sciences, and other sources.

Another way to see that there really is a universal system of absolute moral truths is to realize that all relativistic systems of thought are inherently self-contradictory. If someone says to me, “There are no absolute truths,” my reply is “Are you absolutely sure there are no absolute truths?” In other words, advocates of relativistic systems of thought must start out by (at least implicitly) assuming the very thing they are trying to refute.

The founding fathers were so confident of the universality of the principles of natural law stated in the Declaration of Independence that they held those truths to be “self evident” and appealed “to the Supreme Judge of the World for the rectitude of our intentions.”

A full discussion of the concept of natural law would require book length (and is therefore beyond the scope of this site!) However, readers who want more information on this subject are encouraged to consult any of the following books:

What We Can’t Not Know, by J. Budziszewski.

Legislating Morality, by Norman Geisler and Frank Turek.

The Abolition of Man, by C. S. Lewis.

It should also be noted here that one of the most important rules of scriptural interpretation is that “scripture interprets scripture.” In other words, to arrive at the best interpretation, each scripture should be read not only in its immediate context, but also in the context of what the whole rest of the Bible says. Therefore, the rest of this site does its best to present an overview of what the Bible as a whole has to say on each topic. In this way, hopefully, extremism and misinterpretation of individual passages can be avoided.

[1] The Judeo-Christian moral code can be summarized in the second of Jesus’s two commands given in Matthew 22:36-40 (“Love your neighbor as yourself”), or in the last six of the Ten Commandments. However, to be of the greatest use in helping to govern a nation, the Judeo-Christian moral code needs to be explained and elaborated considerably beyond either of these two summaries (which is part of the purpose of this site.)

[2] As discussed in more detall in the section of this site on Rights of Conscience, the various versions of the Humanist Manifesto begin by assuming, as a philosophical precondition (or in a certain sense, as a matter of faith) that man can live independently of God. The earliest version of the Humanist Manifesto explicitly described secular humanism as an alternative religion, and stated that “to establish such a religion is a major necessity of the present.” Thus, it constitutes religious discrimination (which violates the Establishment Clause of the U.S. Constitution) to allow the expression of secular humanism (or agnosticism or atheism) in the public square, but prohibit the expression of all other religions in our public life.